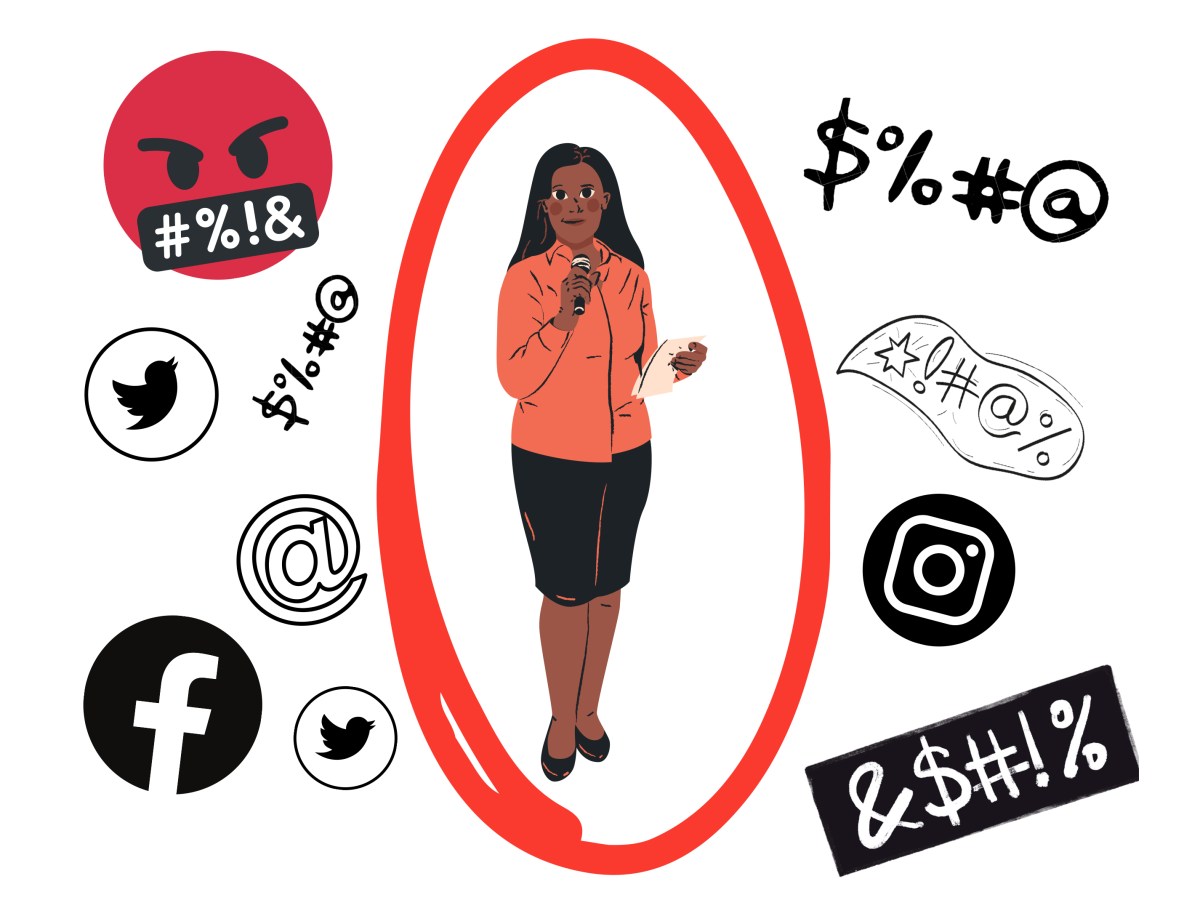

Imagine opening social media, one of the first things you see is an image of yourself naked. For Nora Loreto, it wasn’t the usual kind of hate she’s come to expect online.

“Someone photoshopped me with no clothes at a presentation I gave a decade ago,” says Loreto. “It was really something to see actually. I was like, ‘Whoa, I don’t remember being naked. That’s unsettling and weird, right?’”

Loreto has been a freelance writer since 2012. She has published three books, has a podcast called Nora & Sandy Talk Politics with her co-host Sandy Hudson, and is the editor of the organization Canadian Association of Labour Media, a communications cooperative that represents almost 200 labor unions across Canada.

A UNESCO Report from 2018 mentions that female journalists experience approximately three times more abusive comments than their male counterparts on Twitter, now known as X. The report also mentions how The Guardian examined 70 million comments on its website from 1999 to 2016, and of those comments, roughly 1.4 million were blocked for abusive behaviour. Among the ten staff journalists who received the highest levels of abuse, eight were women and two were Black men where stories written by women received the highest percentage of harassment. The report states the abuse from “trolls” has become an “occupational hazard.” And it’s also difficult to filter through and remove the abusive comments and content because it’s like an “avalanche of abuse across multiple platforms from anonymous sources.” Yet despite the barrage of digital vitriol, at least some journalists contend social media remains a vital tool in their work. Nora Loreto is one of them.

New Opportunities Online

Loreto receives a lot of violent threats as well, and the harassment is daily. Although it doesn’t bother her that much.

“My friends have been way more worried about me. But I live in such a way that I’m somewhat protected,” she says, noting her journalism isn’t read that much in Quebec City, where she lives. Loreto adds, “That allows me to take a lot more risks than I would not be able to take if I was somewhere else.”

She doesn’t let the harassment bother her, partly because she is used to it, but partly because she has better things to focus on. Political action informs her journalism: “I’m part of a group in Quebec City that has fought for public transit and someone vandalized a part of my house, and that was because of my activism.”

Loreto has no issues writing a simple news story, and says, “I can write straight news and be fair and balanced to all sides. But at the end of the day, I think that you can’t look at this country and society and feel like everything is okay.”

The problem was the lack of space to do the critical writing she wanted to.

Sharing a similar sentiment is Erica Ifilll, a journalist and economist who co-host’s the Bad and Bitchy Podcast and has a column in The Hill Times.

“People know when something is wrong and if you want to talk about politics or talk about economics,” says Ifill, “people feel like they’re getting bumped. It’s our job to be like ‘they’re fucking you.’ Journalism is a bit of advocacy. The best journalists are advocates of something.”

Loreto looks back to some of her inspirational role models in times like these.

“It wouldn’t have been as hard if I had been a journalist in different times. Think of someone like Doris Anderson or Michelle Landsberg, feminist activists who were editing The Chatelaine or writing in the Toronto Star [from the 1960s to the 1990s] consistently,” she says.

Unfortunately, Loreto didn’t see eye-to-eye with some of her career inspirations: “The first year of journalism school we were supposed to interview somebody notable and I picked June Callwood. Her advice to me was just don’t write about the activism that you do.”

“There’s no space for left wing voices in Canada,” adds Loreto. “I mean there’s certainly space for centrist voices, which often get called left wing, but it’s really hard.”

Loreto’s feels her career has been affected by her activism, noting, “The fact I don’t hide my politics, there are trade-offs to that. I’m not going to have a real job at CBC.”

This is where social media comes in. When she first moved to Quebec City, not only were her politics an issue but Loreto also faced a language barrier and says, “I had no prospect of work. I had to make my own career because while there is English media here, it’s very, very limited.”

However, she believes she wouldn’t have the career she does now, if it wasn’t for social media

“I think my career would have been very different if I had been a journalist 20 years earlier, but left-wing writers have been systematically shut out of mainstream media. So social media has been the only option for me to work.”

Social Media: A Two Edged Sword

Luke LeBrun, the editor of Press Progress, an independent Canadian news organization, admits he was late to social media

“I thought Twitter was so toxic, then at a certain point I wanted to get involved in more of the brand and some of the conversations that were happening online.”

While he recognizes that social media’s widespread exposure benefits a digital publication like Press Progress, he also notes some of the attention he has attracted isn’t the easiest to digest.

“First of all, these people live stream 90 per cent of their waking lives. I’ve been the subject of a couple of their Facebook lives. I put out a story and they start to vent and fume about me personally,” says LeBrun.

He is talking about Save The Children Convoy. LeBrun stumbled across it by accident when he saw a video of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau being swarmed by protestors.

“I was trying to figure out who these people were and it led me down a rabbit hole,” says LeBrun. “I started finding people who were expressing concern about this plan, Save The Children Convoy.”

“It is actually often far-right media outlets sending their followers to attack other journalists. It’s also worth noting the vitriol seems to be worse when it’s a journalist who is a woman or who is racialized.”

— Emmet Macfarlane

Although LeBrun says he’s not too rattled by the negativity, he expresses concern for other journalists who covers extremism and internet culture.

“You see this with Rachel Gilmore [freelance journalist based in Ottawa] in some of the harassment she’s faced. You know if people are repeatedly talking about you online, it can start escalating.”

LeBrun adds, “This harassment is rooted in these political and ideological movements. Prior to the Freedom Convoy, I didn’t get too many harassing messages.”

But during and after the Freedom Convoy, he said it wasn’t just journalists noticing the increase in hate, but “also a lot of community leaders in Ottawa… who were getting crazy messages or discovering they’re on these Twitter lists.”

While the hostility online is unsettling, LeBrun points out that adversarial relationships with the media are beneficial for some politicians.

“With opposition leader Pierre Poilievre, it’s about creating useful kinds of enemies and then raising money from your most diehard supporters,” says LeBrun, noting that this behaviour is not new.

“Harper had a kind of antagonistic relationship with the media, that was preceded by [U.S. president George] Bush’s relationship with the media too. But I do think Poilievre especially, he and his team have made no secret they want to have an antagonistic relationship with the media.”

Origins of aggression and accountability

Emmet Macfarlane, a professor of political science at the University of Waterloo, identifies the origins of online aggression, who they target and how they escalate.

“It is actually often far-right media outlets sending their followers to attack other journalists. It’s also worth noting the vitriol seems to be worse when it’s a journalist who is a woman or who is racialized.”

Even though it’s possible to track where the harassment originates, holding those accountable isn’t a priority for LeBrun who says, “I never bother reporting to the police because I don’t exactly have a whole lot of confidence in either their ability to investigate these things or to actually enforce any laws.”

Erica Ifill agrees with that perspective stating, “When it comes to the police, a lot of these hate crime divisions are just window dressing. They don’t care.”

Richard Moon, a law professor at the University of Windsor, notes that one of the difficulties about controlling harassment on the internet is that “The Criminal Code provision is just way too cumbersome to deal with the kind of rapid, broad spread of hateful material online.”

Moon says the federal government has been struggling to create legislative routes that address online hate noting that a background paper written by Julian Walker in September 2018 had proposed that “Section 13 of the Canadian Human Rights Act makes it a discriminatory practice for anyone to communicate by telephone, by a telecommunication undertaking or by a computer-based communication, including the internet…”

However, the act was repealed in 2013 and Section 13 of the Canadian Human Rights Act is now missing online.

IMAGE: CONNER BASILLIE

Another issue concerning accountability is the ability to conceal identities. Malinda Desjarlais, a Mount Royal University professor of psychology, says “There’s an element of anonymity where people don’t know you at all.” And when social clues, like eye contact, that allow us to recognize one another aren’t available, she points out, “It gives us a sense of being separated from those people.”

Desjarlais refers to the online disinhibition effect, “which allows us to do things that we would not normally do face to face.” When there’s a lack of eye contact and we are anonymous or invisible online, there’s a tendency to compare ourselves to others “that includes the cyber aggressive types.”

Overall, Desjarlais lands on an ominous conclusion.

“As time has gone on, you see more of [social media] becoming a superficial replacement for what used to be meaningful interactions… and that becomes very dangerous.”

Macfarlane claims that anonymity also delays the process of accountability and says, “This is one of the policy questions that has been raised. Should these platforms have an identity verification process for registering?”

For example, say a troll has been identified, Macfarlane notes, “The authorities can investigate that, but even if you have a sympathetic police working for you, these are drawn out processes… Will charges be laid? Even if charges get laid, how long is that process?”

The lack of accountability adds to the depth of the vitriol, and despite the defiant stance of most journalists, that comes with a price. Jacob Nelson, a former journalist and professor at the University of Utah, notes the impact on journalists saying, “There are risks to the actual profession of journalism in the sense that journalists know there’s a chance they will face abuse if they cover a particular topic.”

He adds some journalists are not able to cover certain stories or do not feel confident enough to be entirely honest in their stories because they don’t want to risk angering potential trolls, which “could negatively impact the journalism we see.”

Importance of community

A UNESCO and International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) survey collected data from over 1,200 global respondents and found 73 per cent of female journalists said they’ve experienced online violence during their work. The survey also showed 20 per cent of journalists who identify as women have been abused and attacked offline in connection with online targeted violence.

Despite the hate and harassment, journalists persevere. Ifill promotes the positive side of social media, in that “we need to understand that social media builds communities.” To illustrate that she talks about renovating her kitchen, and her online community providing support — people dropped off food and gave her “UberEats because they knew my kitchen was being redone.”

She also explains there’s different phases that occur on social media in relation to receiving community support.

“You’re being attacked by email,” says Ifill. “Then you’re being really attacked on social media. Then the third phase is if you have built a community, you got to wait for them to figure out what is going on and they ride for you.”

When emphasizing the importance of community created by social media, Ifill recalls a time when she and some other journalists where targeted in a hate campaign online. When she informed her newsroom and the police on how to handle the problem, she felt “I don’t think they understand it. They don’t understand the difference between an email campaign and a Twitter campaign and all we got from news executives was to stay off Twitter.”

The response from management undermines Ifill’s growth and development as a journalist and says, “Being a woman of colour, that’s the only place [online] where we can get our voices heard. That’s the place that made us, our communities are there.”

Nelson also echos a change needs to happen within the newsroom.

“If your newsroom leadership is primarily white and male, that demographic is the least likely to experience online harassment,’ says Nelson. “If you are a journalist of colour or a female journalist and you’ve been facing a ton of really awful harassment… It is important to make sure if, or when, journalists do get harassed, they have a place where they feel accepted and sympathized with.”

A new horizon

LeBrun feels that Canadian journalism has benefited from social media by democratizing the media and acting as a counterbalance against some of the media concentration that exits. “In some cases,” notes LeBrun, “you are able to break stories and kind of force the bigger outlets to pick it up.”

Ifill also has high hopes for social media in journalism giving it some new life.

“One of the problems with legacy media is what they consider news. It’s very snooty, it’s old air and it needs to breathe,” says Ifill. “TikTok is fun and informative, it has so much potential to be the news outlet.”

She adds, “What we’re talking about is where journalism is now. It’s on TikTok, it’s on Instagram.” Ifill also thinks news executives don’t realize they might have lost out on younger audiences claiming, “Gen X would probably be the last generation that goes to a news website to get news.”

Addressing issues more effectively

Macfarlane wants to avoid the simple approach of simply shutting people down, and refers to what’s known as the Streisand effect, “where attempts to de-platform people actually bring more attention to the hateful speech or make a martyr out of the speaker.”

The name comes from the actress Barbra Streisand, who, in 2003, had a lawsuit against a photographer for taking a photo of her house. She wanted that picture deleted from the internet and sued the photographer for violating her privacy. But when the lawsuit was filed, the picture of the house only had six downloads. Then the lawsuit increased in popularity, and so did the photo online, resulting in more than 400,000 views.

To offset these kind of problems with social media, Macfarlane seeks a more productive means to confront complex issues like hate campaigns. He says, “While hate speech itself is a problem, it’s also mostly a symptom of a problem. We need to get to the root of the problem.”

Macfarlane has seen efforts to improve the systemic institutional representation at the university he works at. He offers an example that if one speaker wishes to speak out against the inclusion of transgender people, there will be speaking events or counter protests where the community comes out to support its trans members.

“This charter values approach is designed to think about ways to react to hate that is not limited to a need to censor or punish hateful speech or rhetoric,” says Macfarlane.

The journalists featured tend to agree that we can’t approach social media with a black and white view — there’s a need for nuance and discourse, and there is a lot of potential for social media to be that place for discourse. They point out social media has allowed for marginalized voices to finally be heard. Instead of putting all our focus on hate, we should be focusing on how to continue amplifying those voices of support and places for community.