After working 16 hours straight, according to healthcare experts, people hit a certain point of delirium. Imagine playing a first-person point-of-view video game; your mind is the controller, and you fall into autopilot. Nothing feels entirely real, and your moods begin to shift. You’re hot, then you’re cold, then you feel nothing at all.

Suppose this is your standard day: 16 hours of work on a film set, but some shifts might even go longer, pushing your body to its maximum while lifting heavy equipment, painstakingly arranging and rearranging props, not knowing if you’re going home in 30 minutes or five hours. You have no choice but to keep pushing. You’re in it for the love of the game and a passion for what you do and who’s around you. That’s life in the movie business.

The Myth of Glamour

Most people believe that working in the film industry is glamorous. Spending your days with celebrities, getting to be creative, and simply making a movie. How difficult could it be? Of course, you do get to avoid the typical 9-to-5 desk job, spend time with like-minded creatives, and create something visually appealing to general audiences, sometimes making a huge amount of money in a short amount of time. Yet, it also involves notoriously long hours, intense pressure, precarity of employment, perhaps no health benefits, and a massive effect on people’s personal lives. The toll on those who work in film range from broken relationships, physical or mental illness, and can even extend to a risk of serious injury or death. Yet there’s not a whole lot of oversight, and attempts at concrete reform haven’t gained much traction over the years despite people speaking out about their turbulent working conditions.

Dr. Paul Heinzelmann, 60, is a primary care physician, self proclaimed SetMD (medical doctor) in Boston, Massachusetts, and director of Safe Sets: Dying to Work in the Film Industry, a documentary that dives into the dangers surrounding the people who give their lives for the magic of the movies. His first experience on set was unique. Heinzelmann was asked to come and tend to a producer with an earache. “There was so much pressure and urgency that this producer was working under that it was easier to just hire me to come to them instead of coming to our office. And for me, that’s kind of a big red flag,” he remembers. “There’s something about that culture where a person’s well-being is treated more like a piece of equipment that you use until it runs out.”

That’s one aspect of the film industry that concerns Heinzelmann, and he recalls that after looking at the producer he was asked by other workers on set to tend to symptoms that they were having on his way out. This made him realize that there is a problem within the film industry, it isn’t limited to earaches or sore arms, and that there was far more going on beyond the surface. “Safety applies to all of those (things), not just physical, but also mental and social (health),” says Dr. Heinzelmann.

The Personal Cost

People who work in the film industry tend to have complicated dynamics when it comes to their social lives. The accumulating strains on relationships are simply a microcosm of their work, and are looked upon as normal. Mory Peterson, 33, who has previously worked in the props department, took a step back from the business to explore other creative avenues, such as photography. He says he knows many people within the sector who are divorced. He chalks this up to the erratic work schedules and lack of time for family. “If film is important to you, you have to find a balance there, or they have to understand that this is what you want to do and this is the commitment that it takes,” says Peterson. “But at what cost?”

Peterson decided the costs of working in film was not worth sacrificing his well-being. He decided to take a step back, and his breaking point is something he remembers vividly. “I was holding a flashlight in my mouth, washing dishes, and pouring this recently boiled, scalding water all over my hands,” says Peterson. “Then my flashlight just flickered and died. I’m standing there in the dark with wet burned hands, and I’m like, ‘What the fuck am I doing here? No part of this is normal life, no part of this really feels worth it to me, this is not the story that I want to be telling’”. Peterson loved being on set, he loved the people around him, but he decided that it was no longer worth it.

Breaking Points

Working in film is a unique experience, and not one that many people get to do. There’s a reason for that. The hours are long, the commitment is titanic, and risk is always looming in the background, something that Peterson is very familiar with. “There’s some instances where, hey, if it’s really windy, maybe a huge lift shouldn’t go up (in the air) and maybe we actually need somebody to say, “I don’t give a fuck about the production”. This is the criteria, and we’re past that criteria. Why is there still a conversation?”

There are many cases of production not taking safety seriously. One of the most publicized events of that nature is the tragic shooting? death of Halyna Hutchins in 2021 on the set of Rust. Safety meetings were constantly skipped over by production, to the point where most of the crew ended up walking off set in protest. In 2014, on the set of Midnight Rider, Sarah Jones and other crew members were shooting a scene on live train tracks. Producers had assured them it was safe and they had permission to film there, but neither of those statements were true. A train came barreling through, leaving the people on the tracks with less than 60 seconds of reaction time, and resulted in the tragic death of Jones. In Vancouver, on the set of Deadpool 2, Joi Harris was brought on to be a stunt double for Zazie Beetz. It was Harris’ first day on set, however producer negligence caused the stunt to go terribly wrong, resulting in her horrific death. When safety isn’t taken seriously on set, crucial mistakes like this can lead to fatal incidents that can be easily avoided if producers took time to go over safety protocols and procedures.

Many workers understand that your job becomes all encompassing. “If you want to work in the film industry you have to understand the film (that you’re working on) is your life,” says AJ Musters, 29, who has been employed on various movie sets for 10 years, ranging from dolly grip to set decorator. Musters, and many countless others within the industry, know that their working hours won’t ever truly align with a partner who is working an office job. In a previous relationship, Musters had to sleep in a separate bedroom from his partner. “We couldn’t share a bed, because I would come home at like five in the morning, and she would wake up at seven in the morning to go to her regular job.”

Just Get Home Safe

The hours during production are rarely ever consistent; one week you’re working the day shift from 5 a.m. to 7 p.m., the next week you’re working the night shift from 3 p.m. until 6 a.m. For Musters, his standard day on set is 16 to 18 hours, which doesn’t leave a lot of time to sleep before he’s back on the job the next day. Breaking that down, if you’re on a set for 18 hours of the day, with an hour-long drive from the set to your home, that’s a total of 20 hours. At that rate, you have a maximum of 3.5 hours of sleep before you’re waking up again to get back to set. Another film worker, who asked not to be identified for this story, expressed how producers would make film employees work 24-hour days if possible, and it already happens. For Musters, his longest day on set was 22 hours. My anonymous source told me that his longest day on set was 24 hours.

“There’s no reason for you to be sacrificing your health and your sanity to get home from work.”

The impact that sleep deprivation can have on the human body is well studied. One paper says that lack of sleep, especially frequently, can lead to difficulty with cognitive performance, decision-making, and issues with long-term memory. These are concerns that Heinzelmann echoes. “It’s really one of the key obstacles keeping people from staying healthy and thriving in their work in this industry. You can’t really have a safe environment when there are long days and short turnarounds, that’s just part of the culture.”

Lack of sleep and “sleep restriction” are commonplace and expected. Sleep restriction occurs when you force yourself to stay awake longer than you should, and when you’re working 14 hour days with quick turnarounds, this happens all the time. Both sleep restriction and lack of sleep can raise your blood pressure, increase your cortisol secretion, and lead to burnout and fatigue. That deep sense of exhaustion is incredibly common in the film industry, and they have been for a long time. Peterson has experienced this, saying he has averaged three to six hours of sleep a day. “Whether you drink eight coffees or not, it has a toll on you, and it starts really affecting your ability to process new information, new schedules changes, new seasons (of television shows),” says Peterson.

Patrick Valentine, 30, who lives and works in Vancouver, and has been in the film industry for ten years as a prop coordinator, art director, and film director. They emphasize how quick turnaround times for long days on set impacts their ability to eat and shower before the next day starts. “You just climb in (bed) and then swap your clothes out and go to work the next day” says Valentine. Even if you’re working in the production office rather than on set you’re still in for a long day. “I fight for being in an office position so that I’m glued to doing a 12 hour (shift),” says Valentine, but that still equates to a 13 hour day once they get home, leaving little time for eating and sleeping.

In his work on sets, Heinzelmann has seen many sleep deprived film workers, and it’s something that deeply concerns him. “If people are chronically tired their focus narrows and they default to the simplest safest mental shortcuts. Their tolerance for risk drops, they become more risk averse creatively and physically. So that sleep itself results in a whole bunch of things. Creativity is one of many. Others are that it results in more accidents, more risk taking, more use of substances to try to stay awake, etcetera.”

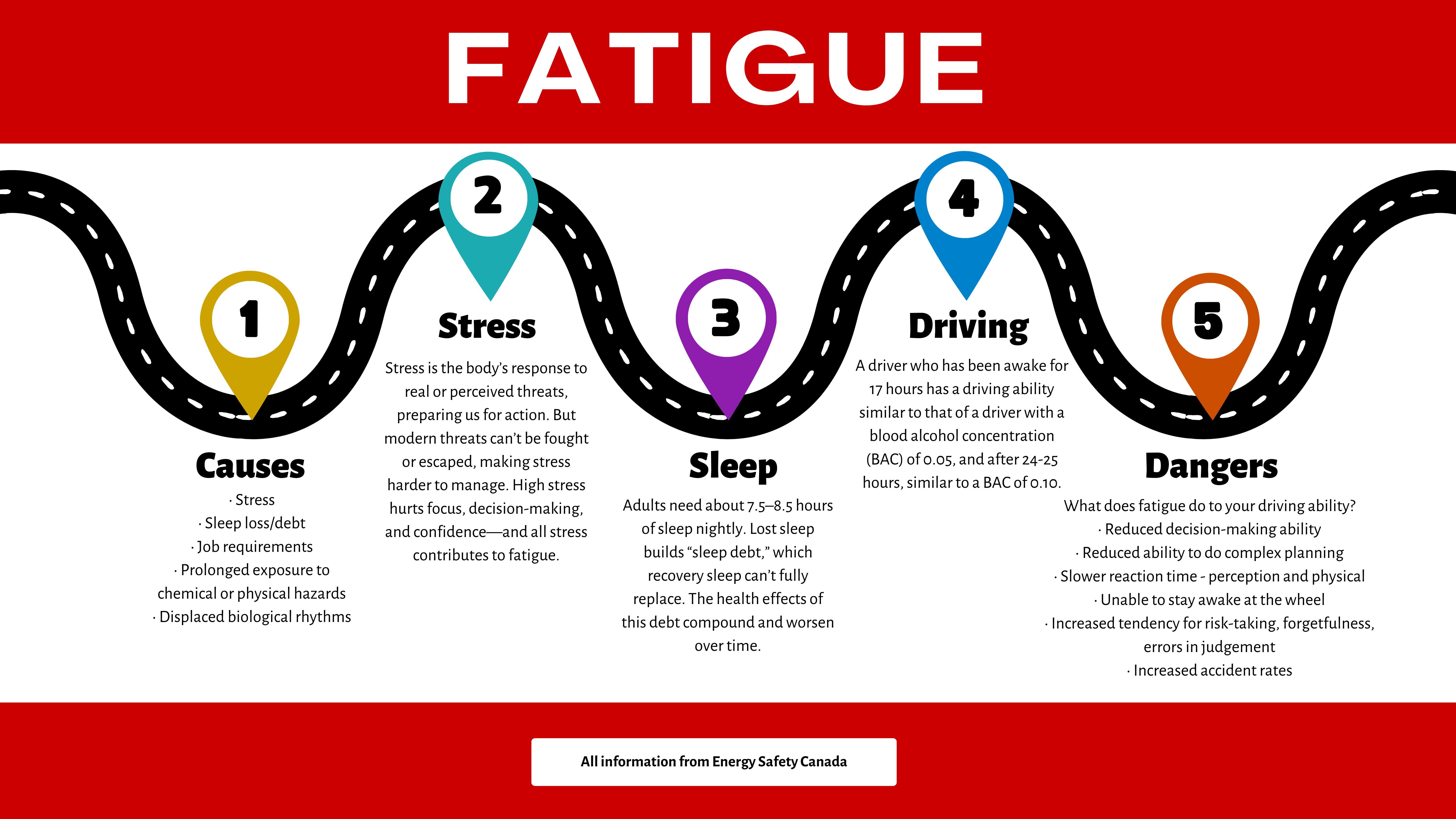

Car accidents on the commute to or from set are almost a given. If you work in film, chances are you either know someone who has been in a car accident, or you, yourself, have been in one. Energy Safety Canada, a company committed to creating and fostering safe working environments, did a study on fatigue, noting that “20 per cent of fatal collisions involve driver fatigue.” Valentine describes a harrowing experience where their fatigue led to a car accident, leading them to rethink how they were treating their body in relation to their work. “I hydroplaned and crashed my car due to sleep deprivation, and that was a really dangerous experience,” says Valentine. “I learned not to rush stuff after that, and in order not to rush stuff I had to start saying ‘no’ to overextending myself. There’s no reason for you to be sacrificing your health and your sanity to get home after work.”

Not everyone gets into a car accident, but many nod off at the wheel momentarily before jolting awake while still having both hands on the wheel. Heinzelmann compares driving while tired to drunk driving. “It’s one of the most underestimated risks in this industry. Driving in a car is monotonous and people will often have these lapses in consciousness where they briefly fall asleep. It’s called micro sleep. If you’re on a dark highway at 3 a.m. after working a 14 hour day, the risk of that being a fatal event is much higher than otherwise.”

The Delirium Conundrum

Just about everyone in the business knows someone who has fallen asleep at the wheel. They say that it’s not a matter of if, but rather a matter of when. People often combat this with caffeine, nicotine gum, blaring music, talking with a passenger or even things like smelling salts and stimulants. There’s a mindset of “whatever works” when it comes to driving while fatigued.

“You’re actually delirious. I thought I saw a deer on the road. That’s the state that you get into,” says Peterson. He considers nodding off at the wheel to be the same as falling asleep at the wheel. “You cease to exist for a second…you feel the tightness of the steering wheel, you just let go a little bit. You disconnect from the road.”

Matt Johnson, 34, has worked in the film industry for 10 years, currently as a digital loader, recalls a time when he and a colleague were driving back to a hotel after a 21 hour day on set early in his film career. “I remember I was having this conversation with him and when we got back to the (car) park, he’s like ‘man I don’t even think I remember anything I said in the last hour’, and I was like ‘oh dude I have no idea’. We couldn’t think of a single subject that we had spoken about in the last hour of the drive home and we just started laughing our asses off.” Though it was funny at the time, Johnson reflects on this, wondering how his colleague was even able to drive a car in that state, and questions the safety of that drive. Yet this is completely normalized, driving home when you’re at the point of dangerous delirium.

“It is impaired driving, and that’s dangerous,” notes my anonymous source, “what about the safety off-set? What about the safety of getting home? You could put other people in danger.”

The Missing Safety Net

Peterson says that production companies can offer shuttles to their cast and crew, but they’re typically from production offices that are still an hour’s drive away from someone’s home. If you’re driving for an hour on the highway after working a 16 hour day it is inevitable that at one point you’ll either come close to nodding off at the wheel, or you will. In terms of road safety, every second counts. “I’m not saying that they never offer anything, but I think we have to have a huge conversation on hotels for crew and sleeping arrangements,” notes Peterson.

Kristin Breitkreutz, 28, who has worked in the industry for five years as a photographer, trainee coordinator, and assistant production coordinator echoes that shuttles would be nice to have on sets further outside of the city, something incredibly common in Alberta. “There’s no obligation to offer shuttles, but it can still be such a long drive for some people so I’d be nice if we could offer that more because at least with the shuttle you can sleep on it if you want,” says Breitkreutz. “All you have to do is get back to the city, hop in your car and drive, hopefully, 10 minutes home.”

Chasing the Magic

So why do people continue to work in film? You deal with an immense amount of stress, intense long hours, and genuine risk constantly. Every single person I spoke to mentioned the closeness of the friends they have, and the different things that happen on a day-to-day basis. “It’s always something new, we’re constantly changing, constantly doing new things. And it’s exciting,” notes Musters. Having love for the movies is a big part of it too. You’re on a film set, everything is organized chaos, and even if you’ve been there for 13 hours already you still know you’re contributing to something amazing. “You have these pockets of really freeing moments where you’re like, ‘There’s no fucking way I’m getting paid for this,’” says my anonymous source. “I feel like all the negatives I’ve talked about go right out the window when I’m there.”

Valentine values the unique experiences that you get to have on set, quietly shadowing people you admire, seeing the process behind the production and having a first-row seat to a project bloom from an idea to an actual tangible reality. “I just worked on a horror movie with one of my all-time favourite directors. Being able to watch them do their process, I learned more in those two months than I did in two years of school,” says Valentine.

Love for the film industry can’t change the dangers of it, though things have gotten better in the past 25 years, there is still so much work to be done. My anonymous source says, “It’s fast paced, it’s higher stress, but every day is fulfilling. Once you complete that day…there’s a sense of real accomplishment there. I think a lot of people chase that. Even when you finish a show, it feels amazing. I think a lot of that has to do with how difficult the actual journey is to get there.”

Perhaps a difficult journey need not be quite so dangerous.