The election of Donald Trump spawned a rise in alt-right ideologies, defined by policies such as normalized Islamophobia, even a stark rise in anti-immigration ideas as seen by Trump’s wall. These ideologies inspired a wave of associated memes on social media, such as Pepe the Frog, which became a symbol of bigotry. Although memes like Pepe were intended for humour, it often was at the expense of other minority groups, hiding beneath that thin veil of laughs to perpetrate hate.

At the time Niamh Hernandez found the memes funny, and laughed about them with her friends. Hernandez is a transgender and pansexual woman from Texas, who embraced meme culture as an aspect of her identity in high school, despitememes often targeting people of her own identity.

“Me and my immediate friend group were all very edgy, as you might say. Like, we would joke about whatever, whether it be offensive or not,” she says.

Those who follow and study the alt-right make the connection between toxic memes, the flourish of homophobic and racist ideal, and ultimately discriminatory government policy and violence against marginalized groups.

Hernandez learned precisely how influential and toxic those memes could be as they began to spread, and one of her close friends at the time, Brendan Sophabmixay, seems to have internalized the misinformation in memes.

“We would joke about whatever, and he would start joking about some things that like, yeah, like we would laugh at and all that. But then it became apparent to us that it probably wasn’t just a joke,” she says. Hernandez felt the frustration of her group of friends, recognizing Sophabmixay’s slide into the alt-right mind-space as he ranted and took stances that were factually incorrect.

Sophabmixay frequented online spaces such as Reddit, Instagram and YouTube that formulated memes built at the expense of LGBTQ+ people, slowly embodying the alt-right mindset. “Most of them were like, they made a stance like, like that we’re like, make the light or make fun of LGBTQ people, primarily homophobic and transphobic type of content,” he says, “and then like, they would take a stance where like, it’s just jokes, and then they would use that as a cop out.”

He felt that the rise in bigoted thoughts was encouraged by the systems he used, and fed into a feedback loop designed by the systems to ultimately push more content. YouTube was especially bad, where hateful content was introduced into his feed and regular media consumption habits.

“I feel like everyone uses the buzz word algorithm, but I genuinely do think that the YouTube algorithms did have a pretty large factor in how that stuff came to fruition because it was oftentimes no one really went out of their way to be bigoted or have these types of mindsets.”

Sophabmixay found that his life outside of the internet enabled this behaviour – and made it OK because there were no real consequences. “There was certainly a lack of accountability, and I live in a predominantly white area so I didn’t really have to be held accountable for the stuff that I found funny or the memes I would spread to other people.”

As Sophabmixay found humour at the expense of others, Hernandez and her circle began to contemplate the relationship they had with him.

online and in-person.

PHOTO: SUPPLIED BY ERIN GUTIERREZ

THE EXPERT’S TAKE

Dan Prisk, a student pursuing a master’s in arts at the University of British Columbia, whose interests involve the resurging alt-right scene, has seen how persistent exposure to radical ideas often leads to the acceptance of them.

“When done often enough, such as if you’re regularly making Nazi jokes, those ideas start to imprint themselves and start to sort of reshape the way you really think,” he says, “that humour in that sense, and that kind of attachment to offensive humour,does help to shape that and help to draw people in and help to make it feel more normal.”

Erin Gutierrez, a lesbian woman who has a long history with LGBTQ+ communities both online and in-person, talks about the role social media plays in further internalizing bigoted messages in people as they find comfort in their own beliefs among like-minded peers.

“If I’m on Facebook, looking at memes, and maybe different groups that share these memes and have a bunch of people agreeing with what I think, my subculture might seem bigger than it actually is, and it sort of validates your opinion,” she says. “It makes it increasingly difficult to find other people’s opinions, because when you’re not looking for it, you’re just stuck inside this echo chamber of just what you know, and what you like.”

The principle of a hateful meme often relies on a simple idea that creates a powerful yet deceptive mode of media to influence people.

Maxime Dafaure, a PhD candidate at the University of Paris-Est in France, studies and writes on the content and impacts of memes in alt-right headspaces, bringing an expert’s perspective on the medium’s misinformation.

“Memes are very powerful propaganda tools. Because obviously, they’re very easy to understand. So, you’re just going to fall on one meme. And it’s a simple message,” he says. ”And then you don’t have to think about it for hours, you just have to look at the picture to look at the text. And the subtext is very often quite easy to understand.”

The ideas behind memes become increasingly normalized when it’s enjoyable to consume, which can then quickly attain community appeal, Prisk says.

Dafaure explains that ultimately, these memes are human rights violations, attacking the LGTBQ+ community, “so they are not individuals who make their own rational decisions, but they are in fact, sick people who need to be treated into normalcy.”

Memes generate a shared language, Prisk says, where the ideas of generalizing LGBTQ+ people as sick or illogical become further elevated by the safety of the echo chamber.

“That sense of feeling makes people attached and feeling at home in a movement is a really strong thing that draws people in further and gives them a place to be, especially if you’re already comfortable being around people who understand your inside jokes.”

The message of a meme depends on what the creator wants to criticize, creating anti-LGBTQ+ memes using ignorance as a platform for bigotry. The efforts to be validated and accepted in society by trans and queer peopleare often challenged in the alt-right world Dafaure says, even as LGBTQ+ communities become more broadly accepted in society.

“The new major enemy is queer and trans people, which are clearly the main targets of those new contemporary anti-LGBTQ memes,” he says, “That’s maybe because homosexuality is now more widely accepted in society, whereas the issue of gender is still very hard to grasp for a sizable part of the population.”

When an idea is hard to grasp, people often don’t take the time to fully understand the concepts at play, leading to further discrimination. “So that obviously makes trans people easier targets because it’s easy to mock something which you don’t understand and very often do not even try,” Dafaure says.

Hernandez saw the ignorance develop in Sophabmixay with the normalization of the hate found in memes, thanks to the misinformation spread by memes. The lack of understanding can quickly snowball into not just invalidation online, but real-world physical violence, or injustices in the legal system through the passing of laws, for example, against trans athletes and LGTBQ+ education in schools.

DIGITAL ILLUSTRATION: DONALD TRUMP JR INSTAGRAM

WHAT DOES IT LOOK LIKE IN REALITY?

The constant exposure and normalization of bigotry in memes grants it a terrifying avenue in the real world, by way of integrating itself with politicians and public figures. With media discourse over Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, politicians have become increasingly engrossed in popular culture, which helps to normalize harmful ideologies in their campaigns.

“I think maybe it’s even more alarming than individual or group-based online harassment,” Dafaure says. “But I think there is a very dangerous feedback loop between the memes and the discourses by right-wing politicians and media channels.”

“It’s not just cultural, but it gets turned into legislation and those legislations hurt LGBTQ+ communities and other minorities on a state or a national level, he says. “And that I’m thinking about many laws throughout the United States which now, for example, prohibit the teaching or simply talking about LGBTQ+ issues.”

Defaure is speaking to the recently-passed bill HB 1557, or the, “don’t say gay,” legislation recently passed in Florida. The law makes it so discussion surrounding sexual orientation is prohibited from kindergarten to grade three.

Outside of legislation, the fear of physical violence is at an all-time high as anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment equates them to pedophiles, for example. Dafaure says it’s a familiar homophobic trope.

“With gay people, there’s always been this kind of vicious link between homosexuality and pedophilia and now it’s the same with queer and trans people.” It’s an anti LGBTQ+ sentiment that’s targeted these communities for years. It attempts to invoke a sense of moral panic, Dafaure says.

One such example is PizzaGate, a debunked conspiracy theory that suggested the Washington, D.C. pizzeria Comet Ping-Pong was secretly running a pedophilia ring for American politicians. Gutierrez explains that the conspiracy theory had homophobic ideas built in, as alt-right extremists targeted the restaurant because of it welcomed LGBTQ+ customers.

“It was very pro-LGBT, and someone actually went out with a gun to this pizza place. And luckily, no one was hurt, he was apprehended before anything happened,” she says. However, as the internet continues to normalize hateful sentiments due to memes, the human rights of LGBTQ+ will continue to feel besieged.

“There’s also a sense of community and attachment, and like a lot of social movement analysis looks at the ways in which a strong decider of people’s engagement in social movements is having a social connection to the movement.”

The sense of community creates a situation where groups of people are able to impose hate, ultimately invalidating LGBTQ+ people. Dafaure’s research delves into the content of the dehumanization process that memes often invoke as they push bigoted content on social media platforms.

“I think one of the major issues with those internet memes, which are targeting LGBT people are, to some extent, or groups of minority people is this kind of dehumanization is kind of depersonalization,” he says. “To the extent that you’re only seeing the stereotypical image of the group, instead of trying to, to understand or to admit the actual image of individuals which are targeted by the memes.”

THESE MEMES MATERIALIZED

His research identifies how malicious concepts, such as gender invalidation, contained in memes ultimately strive to invalidate LGBTQ+ groups with the added tool of weaponizing stereotypes. “You’re going to see caricatures of LGBTQ people as exhibiting psychological or physical problems,” he says. Anti-LGBTQ+ memes seek to cause pain and insecurity, using this simple medium to create disdain for the community.

“So physically, they’re often presented as ugly, overweight, and to some extent, even inhumane, or monsters that are basically whatever they think is outside the norm,” he says. “And psychologically, they’re going to be presented as irrational as ‘I’m angry, fragile’.”

These memes attempt to pathologize – the idea of regarding something as psychologically strange and unhealthy – LGBTQ+ peoples.

“So, you’re going to have lesbians which are painted as angry men-haters, while queer or trans people are depicted as being mentally ill.”

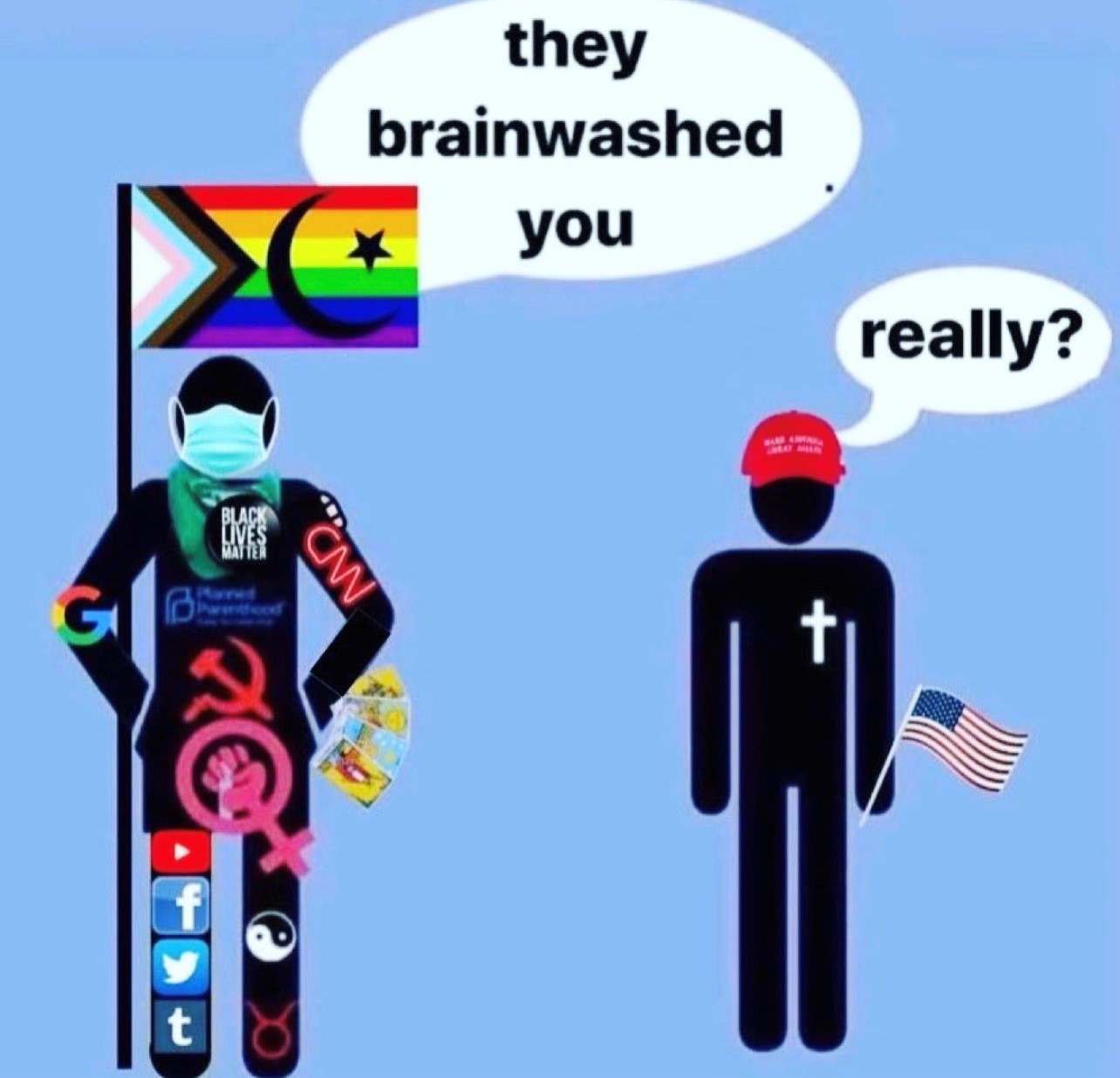

One meme in question, originating from Donald Trump Jr., describes black silhouette standing on the left of the screen, adorned in LGBTQ+ flags, Black Lives Matter and Feminism symbols, and social media icons with a thought bubble stating to a figure on the right “they brainwashed you,”, as they have a MAGA cap, cross on their chest and holding an American flag, to which the latter sarcastically remarks, “really?” A case in point, the meme invalidates those supporting LGBTQ+ and other social movements, treating them as irregular and wrong – while the traditionalist is morally righteous.

hese attacks against LGBTQ+ communities have continued to grow in recent years as well. In 2019, Statistics Canada reported 263 incidents of hate crimes against LGBTQ+ peoples, which is a 41 per cent increase from 2018. There are calls for greater accountability of the platforms that enable the violation of human rights.

PHOTO: SUPPLIED BY NIAMH HERNANDEZ

HOW DO WE MAKE PEOPLE MORE ACCOUNTABLE ONLINE?

Social media accountability is extremely contentious, due in part to the inability of the Internet to effectively moderate, monitor and remove hate speech and bigotry from its platforms. Sophabmixay spoke about how accountability is critical for his own past, describing how the lack of it made it extremely easy for him to become comfortable with alt-right doctrine.

However, Hernandez and Gutierrez both agree that at the end of the day, accountability is something that doesn’t necessarily have one solid solution, as progress has been slow. In 2021, six scientists reported in the article, “HateCheck: Functional Tests for Hate Speech Detection Models,” how state-of-the-art hate speech detection models are strained under AI-led protocols, in which four utilizations of artificial intelligence moderation exhibited critical weaknesses, such as over-sensitivity to specific terminology. Even today, AI fails to understand the context of a situation.

“I don’t think anything could be done online,” Hernandez says, “I feel like it falls into a grey area. If websites do choose to ban certain communities or people with very extremist agendas, you could argue that’s censorship.”

Gutierrez agrees. She understands the difficulty with attempting to ensure hate speech is minimized, especially in an online environment. “I think it’s difficult because it’s so hard to monitor so many users. And we’ve seen companies try to create algorithms, and they’ll sort of backfire, like with YouTube, it was demonetizing a lot of LGBTQ+ creators.”

Hired teams of moderators is often a solution media-platforms such as Reddit or Instagram take to combating hate speech, dedicating jobs and money to ensuring users follow their guidelines to stem bigotry.

However, it’s not as if options don’t exist to ensure accountability, but they involve a more grounded talk, one on one with someone. Dafaure emphasizes this, as it’s important to keep the conversation engaged to ensure that people are able to halt the rise of extremism.

“It’s essential to still have those conversations and to try not to shut off immediately when you see somebody who is beginning to go down this line, this pipeline, and vital have those conversations.”

With Hernandez and Sophabmixay, a conversation is what the two needed to repair a friendship that slowly descended into disarray, that may have caused a split in their friend circle. “We sat down and talked to him like, ‘Hey, you don’t really believe that? All that stuff you’re talking about, right?’ We kind of had to have a little debate with him,” she says. “More and more we kind of not shamed him for it, but corrected the things he said. The more times that we would hang out, the more he just kind of steered away from that side of thinking.”

Having had those discussions, Sophabmixay recognized the misinformation of LGBTQ+ people and alt-right ideology that he’d been internalizing, he says. “I’ve got pretty good at recognizing when there’s something that’s genuinely satirical, and then when something like is being targeted, something’s a little fishy.”

Thanks to their intervention, what could have been an alienated friend was someone who recognized the flaws in his mentality. “He’s still part of our friend group, but he definitely doesn’t think that [alt-right] way. He doesn’t joke that way,” Hernandez says.